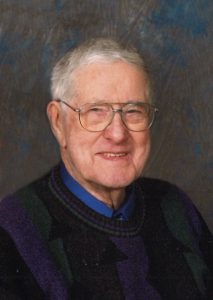

Corporal Gordon William Foster

Corporal Gordon William Foster was born on November 23, 1920 in Waverly, IA and died April 23, 2016 in Waverly, IA.

Gordon William Foster entered the United States Army on July 17, 1942, in Fort Des Moines, IA, served during the World War II era and reached the rank of Corporal before being discharged on June 8, 1945 in Jefferson Barracks, MO.

Gordon William Foster is buried at St. Paul's Lutheran Cemetery in Waverly, Iowa and can be located at

- Wounded in Action: Yes

WAVERLY (KWWL) –

WAVERLY (KWWL) –